Role-Playing Games in the Renaissance Court

Is AIDungeon a game? On the one hand, it is fun, and involves taking turns in a structured environment. On the other hand, there’s no victory condition, no score, and surprisingly little structure. It may be illuminating if we compare to some similar activities.

Is AIDungeon a game? On the one hand, it is fun, and involves taking turns in a structured environment. On the other hand, there’s no victory condition, no score, and surprisingly little structure. It may be illuminating if we compare to some similar activities.

One way of looking at AIDungeon is as a development of what is known as a Text Adventure (a type of interactive fiction) or a Role-Playing Game. We usually think of both genres as beginning in the 1970s. There are some precursors, though, that date back to the Middle Ages. One of them is literally called The Game of Adventure (Le Jeu d’Aventure). Although the history of role-playing games is usually traced through the history of war games (from Chess through tabletop wargames like Kriegsspiel to Chainmail, the immediate precursor to Dungeons and Dragons) there is a parallel thread that focuses mainly on the role-playing aspect, mixed with sources of randomization like cards or dice.

Le Jeu d’Aventure was played in the evenings at court beginning in the late 13th century. Players would roll dice to determine what role they would take, a kind of early random character generation. The roles were written out as short poems, and the players would each pretend to be the person described in their poem. The fun of it was in being witty and jointly creating a story, often filled with innuendo and playful courtly intrigue.

A later game called Ragman’s Roll, or Ragemon le Bon, was played similarly but instead of dice, ribbons were attached to the poems and wrapped up in a long scroll. Each player would choose a ribbon and trace it back to find who they would play. The English word rigamarole derives from this practice.

“All early courtly games of chance, as far as we know, included a mixed company of players (both men and women); only later in the fifteenth century did some of them develop into strictly women’s games. Players might have played Ragemon le Bon in a number of different ways: players may have copied stanzas onto pieces of parchment with a seal and string attached, since “Ragman Rolls” (rolls of deeds on parchment) likely inspired the mechanics of the game. Alternatively, players may have chosen a fortune at random from the manuscript by attaching a string to the margin or by using their fingers to point to a fortune. This divination mechanism differs from other medieval literary games such as Chaunce of the Dyse, which uses three dice instead of string to dispense fortunes to players. Good fortunes typically depict riches, favorable character traits, success in love, courtly behavior, eloquence, and fame, while misfortunes highlight the player’s fickleness, folly, gluttony, danger, pain, or other foibles. Through this nonlinear, interactive reading/play experience, the collection of character-defining fortunes given to players would generate an emergent story that could change with each new iteration of gameplay; like our modern role-playing games, medieval players became protagonists immersed in the game’s imaginary world…”¹

A descendant of this game, with a slightly distorted name, was played in Little Women during a visit with some English children:

Miss Kate did know several new games, and as the girls would not, and the boys could not, eat any more, they all adjourned to the drawing room to play Rigmarole.

“One person begins a story, any nonsense you like, and tells as long as he pleases, only taking care to stop short at some exciting point, when the next takes it up and does the same. It’s very funny when well done, and makes a perfect jumble of tragical comical stuff to laugh over.”

We have found that many of the heaviest users of AIDungeon use it as a way of jointly telling a story with the program, in the same way that these children were jointly telling a story with each other. A lot of the fun of the game comes from the surprising humor of the other players (or the program) taking the story in an unexpected direction.

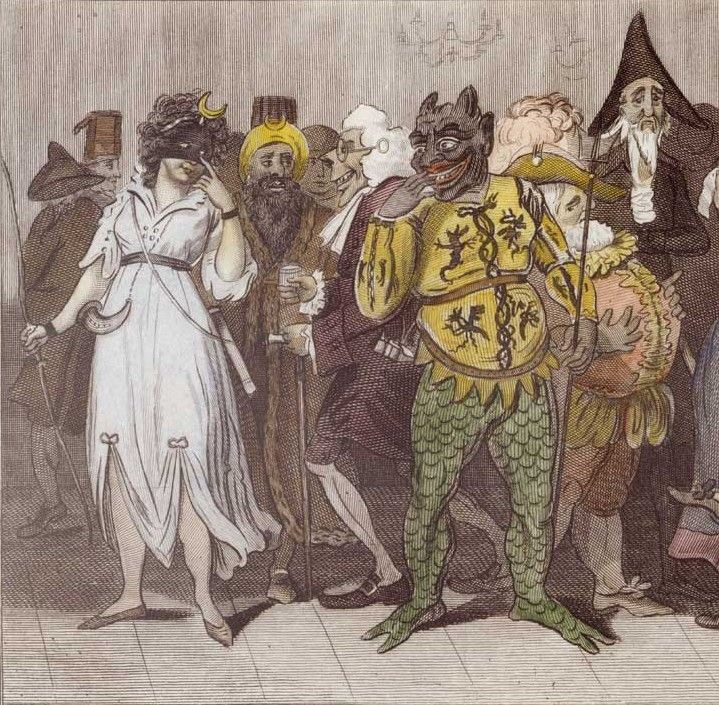

A masquerade ball is a familiar courtly diversion. Games like Ragman’s Roll or Le Jeu d’Aventure were similar to a masquerade, in that they allowed the players to pretend to be someone else, allowing them to say things they couldn’t say out of the context of the game.

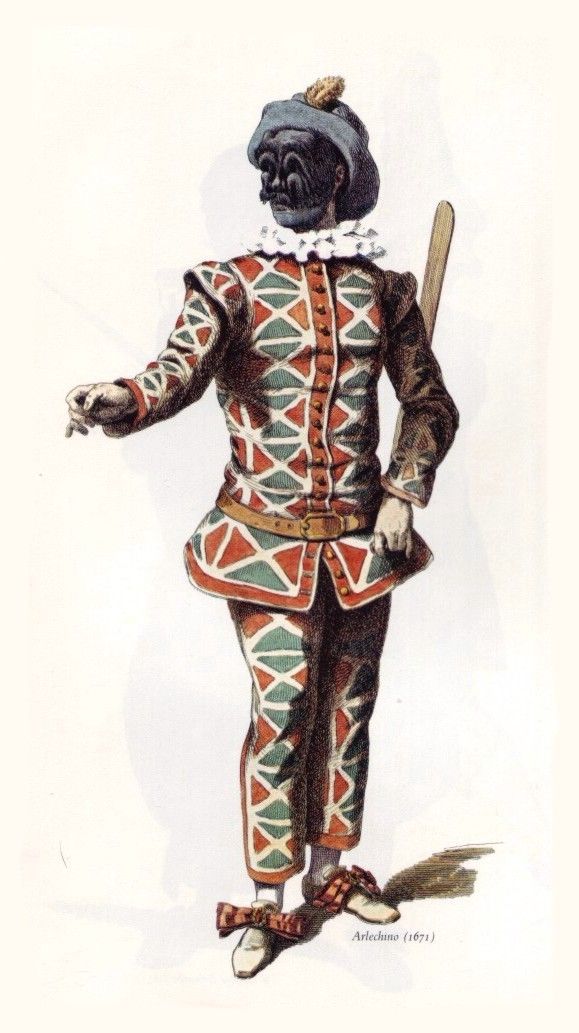

Another role-playing game that was popular during the Rennaissance was the Commedia dell’arte. This was often acted out by a troupe of improvisational players, but it could also be played as a kind of parlor game: Goethe, for example, depicted it in this context. The players would take on particular well-defined roles — the trickster clown Harlequin being the best known today — and improvise scenarios.²

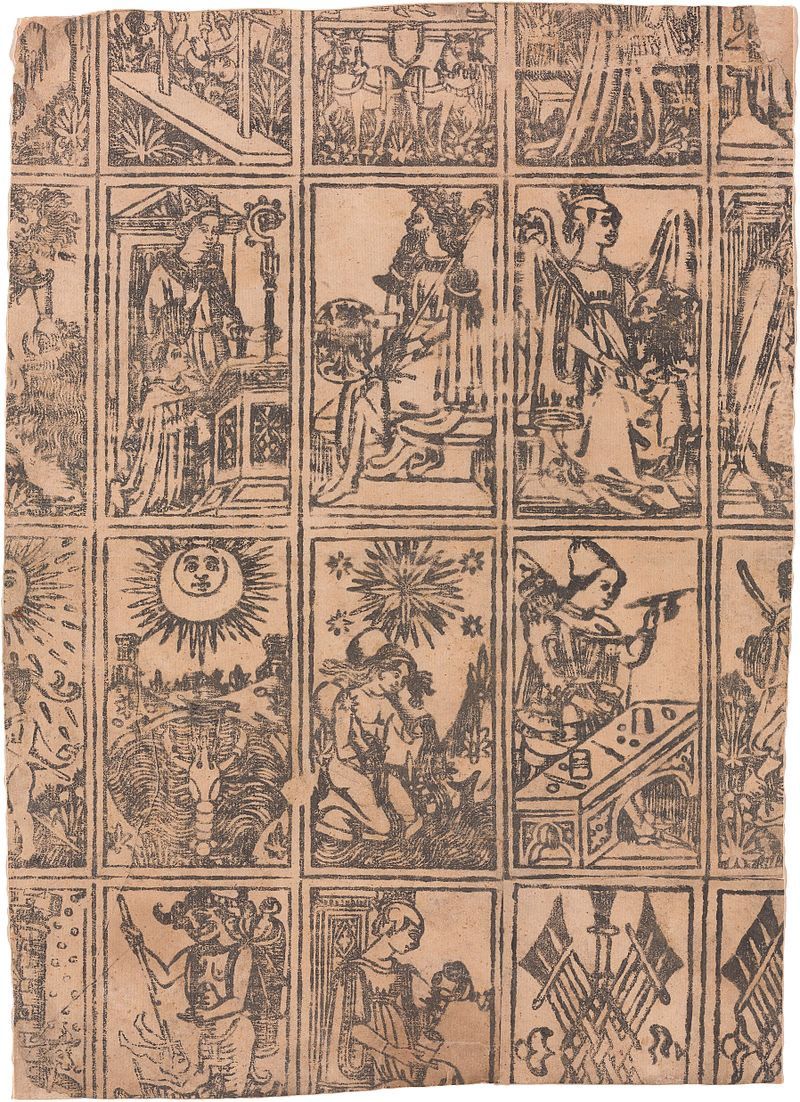

Although today we think of Tarot cards as being used for divination, they were used for a variety of court games — sometimes simply as playing cards for games similar to Hearts, but sometimes as a randomized source of inspiration for role-playing:

“ For all the magnificent entertainments we associate with that age, by and large the days of a Renaissance courtier were plagued by long empty hours and to counteract the boredom, courtiers often gathered to play games. One such game, which became available in the early 15th century, was the Tarot. Beautifully crafted decks started spreading from court to court like wildfire, their popularity boosted by the visual appeal of their art and by the variety of activities they could mediate. The Tarot deck could be used to play trick-taking games; alternately, courtiers could use it for social, content-oriented games. In this version, players would draw cards and take inspiration from the illustrations to produce witty remarks, elegant metaphors, and perhaps improvise a short poem. A conversation would follow in which the participants could choose to speak in their own voice or play a fictional role, pretending to be a character related to the contents of the cards. This style of play seems to anticipate several traits of modern role-playing games, and we have plenty of evidence that its original players tended to perceive it as a form of playable storytelling. Matteo Maria Boiardo, one of the most respected poets of the 15th century, wrote a series of tercets to be transcribed on Tarot cards, expanding the symbolic and narrative potential of the deck. These were not poems about the game but poems for a game, and they were intended as components of a social and creative activity… The famous satirist Pietro Aretino composed a philosophical dialogue in which the speakers are a card maker and a mysteriously sentient deck of cards. Appropriately titled The Talking Cards, the text illustrates how Tarot decks had come to be seen as effective tools to create meaning, to the point that they could be imagined as partners in a conversation! If one was around the same courts in the 16th century, one could also play other games that involved mating narratives and playing a role. In one of these activities the players would pretend to be wizards, and would describe the palaces that they could create with their spells; in another, a participant would pretend to be Charon, while the other players would be souls of dead lovers and would explain to him how they met their fate. Castiglione wrote in his Book of the Courtier that games of this kind took place almost every evening at court…”³

AIDungeon is a realization of the impulse behind “Talking Cards.” Divination techniques, though useless at predicting the future, were a kind of early technology for the automatic generation of sequences of symbols that could be interpreted as if they had meaning. Although AIDungeon is built on a much more sophisticated and responsive technology, in both cases much of the interest comes from the willing choice of players to imbue meaning into the stochastic storytelling.

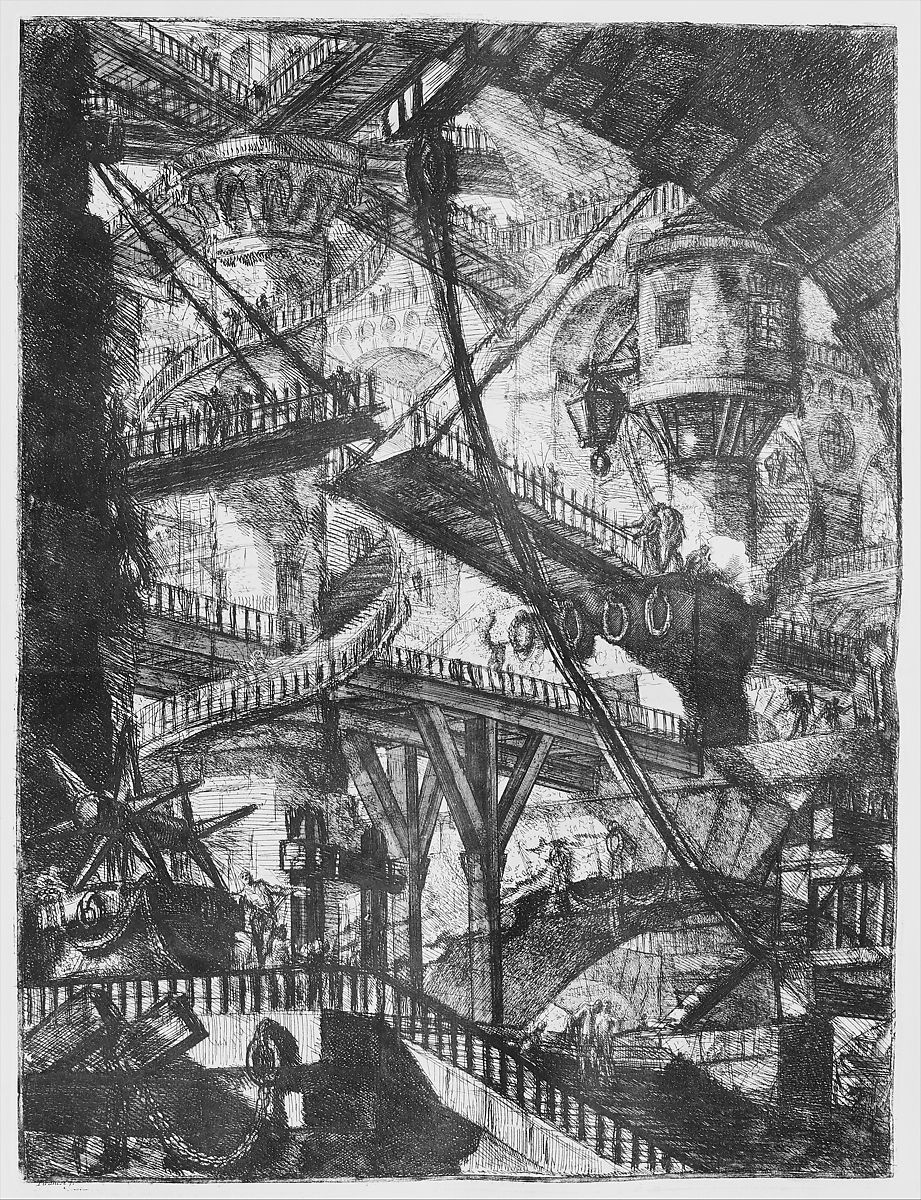

Roleplaying and text adventure games are not just about assuming a role. They also include creating imaginary worlds to play in. Although not associated with games as such, medieval and Renaissance writers used a memorization technique that involved carefully imagining palaces, caverns and dungeons full of strange creatures, called the Ars Memoria. The method emphasized the importance of creating an imaginary space, a memory palace, filled with bizarre or shocking things. St. Augustine wrote about the endless underground spaces of memory in his Confessions:

“Behold in the plains, and caves, and caverns of my memory, innumerable and innumerably full of innumerable kinds of things… over all these do I run, I fly; I dive on this side and on that, as far as I can, and there is no end.”

As Mary Carruthers pointed out in The Craft of Thought, the Ars Memoria was primarily conceived as a tool for creative invention, rather than a means of rote repetition. Medieval authors used the analogy of the imagination as a machine (a new, rare word in those days, meaning in this case a building crane), a Machina Memorialis, that is only capable of building if it has stone blocks (memorized items) to work with:

Medieval memoria was a universal thinking machine, machina memorialis — both the mill that ground the grain of one’s experiences (including all that one read) into a mental flour with which one could make wholesome bread, and also the hoist or windlass that every wise master-builder learned to make and use in constructing new matters.

There seems to be an easy parallel with the notion that in order for GPT-3 (itself a literal machina memorialis) to be inventive, it was first necessary that it read widely.

Closely associated with the Ars Memoria is Ramon Llull’s Ars Magna, later known as the Ars Combinatorica, a method for generating ideas mechanically. It involved concentric paper disks that could be rotated to provide infinite combinations of ideas.

The parlor games, the memorization techniques, and the combinatoric invention all have in common the goal of setting apart a conceptual space in which people can construct meanings together from selected fragments of thought. And perhaps this is the best way to understand what AIDungeon is. It’s an entertaining way of creating stories together with the help of little pieces of story that have already been gathered.

¹ Serina Patterson “Sexy, Naughty, and Lucky in Love: Playing Ragemon Le Bon in English Gentry Households” in Patterson, S. (Ed.). (2015). Games and gaming in medieval literature. Springer

² Morton, Brian. “Larps and their Cousins through the Ages”. In Donnis, Gade & Thorup (ed.). Lifelike. Knudepunkt 2007

³ Storytelling in the Modern Board Game By Marco Arnaudo (Introduction)